適配器模式

概述

這一章我們通過對適配器模式

(Adapter Pattern)

的講解來繼續我們對設計模式的學習。

Adapter

模式是一個經常使用的模式,正如你將會看到的那樣,她常和其他模式一起使用。

在這一章里:

l?????????

我們將學習到什么是

Adapter

模式,她有什么用,以及怎么用。

l?????????

在章末的時候將會有

Adapter

模式的主要功能的總結。

l?????????

通過

Adapter

模式演示多態的使用。

l?????????

演示用

UML

圖來表示不同層次的細節描述。

l?????????

我在實踐過程中的一些對

Adapter

模式的觀察和思考,還會將

Adapter

模式和

Facade

模式進行對比。

l?????????

Adapter

模式簡介

在

GoF

的經典著作《設計模式》中指出:

Adapter

模式的目的就是將類的接口轉換成客戶對象需要的接口,

Adapter

模式使原本不相容的接口變的相容。也就是說我們有一個可以滿足我們需要的對象,但是她的接口卻不是象我們所期望的那樣,而我們現在所需要的就是創建一個新的接口,讓原本的接口能夠滿足我們的需要。

Adapter

模式詳解

要理解

Adapter

模式最簡單的方式就是看看她實際應用的一個例子。假設有如下的要求:

l?????????

創建一些代表著

點、線、方形

的類,并包含“

display

”

(

顯示

)

這個方法

/

行為。

l?????????

客戶對象不需要知道正在使用的對象是

點、線

還是方形,只需要知道是一種形狀

(shape)

就可以了。

換句話說,我需要把這些確切的點啦、線啦、方形啦等等用更概念性的語言類概括起來,也就是

顯示一個形狀。

當我們在完成這個例子的時候,我們可能會遇到這樣的情況:

l?????????

我們想用一段子程序或者說一些別人已經寫好了的代碼,因為這些剛好能夠完成我們所需要的某些功能。

l?????????

但是,我們又不能把這些程序啦、代碼啦直接放到我們自己的程序里面去,

l?????????

因為這些程序、代碼的接口的調用方式和我們期望的又不一樣。

也就是說雖然當前的系統里有

點、線、方形等等這些對象,但是,我的程序僅僅需要把他們統統當成是一種形狀這就足夠了。具體是點、線、還是方形,我不感興趣。

l?????????

這可以使得我的程序可以用一種方式來處理所有的“形狀”,這樣,就不必再去考慮這個

點

和

線

他們有什么不同之類的問題。

l?????????

這種方式還可以讓我以后可以在不改變現有的使用方式的情況下添加進新的具體形狀。

這樣,我們就需要用到

多態

(polymorphism)

。就是說,我的系統里會有各種各樣的具體形狀,但是我可以用一個通用的方式來操縱這些所有的形狀。

這樣,客戶對象就可以簡單地告訴這些

點、線

讓他們在屏幕上顯示出來,或者從屏幕上消失。這些

點、線

他們自己會知道自己該怎么樣的去顯示或不顯示,不需要客戶對象去考慮這個問題。

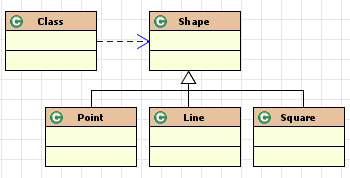

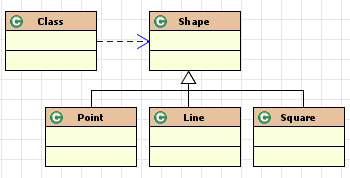

要達到這點,我們先創建一個

Shape

類,然后從她派生

(derive)

出一些代表著

點、線

等具體形狀的類。請參看圖

7-2

。

圖

7-2 Point

、

Lines

、和

Square

都是一種具體的

Shape

。

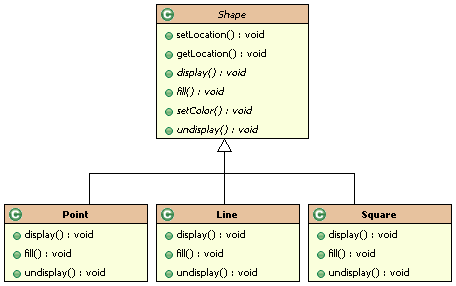

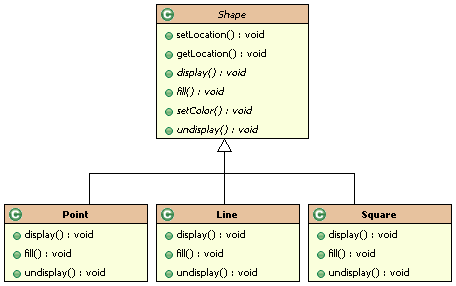

首先,我們必須給

Shape

類確定一些她將會提供的具體行為。我們可以通過在

Shape

里面定義一些抽象接口然后在

Point Line Square

等類中具體實現這些接口的方式來達到目的。

我們給

Shape

提供以下的一些方法:

l?????????

指定

Shape

在屏幕上的位置

l?????????

獲取

Shape

在屏幕上的位置

l?????????

讓

Shape

在屏幕上顯示

l?????????

對

Shape

進行填充

l?????????

給

Shape

指定一個顏色

l?????????

讓

Shape

從屏幕上消失

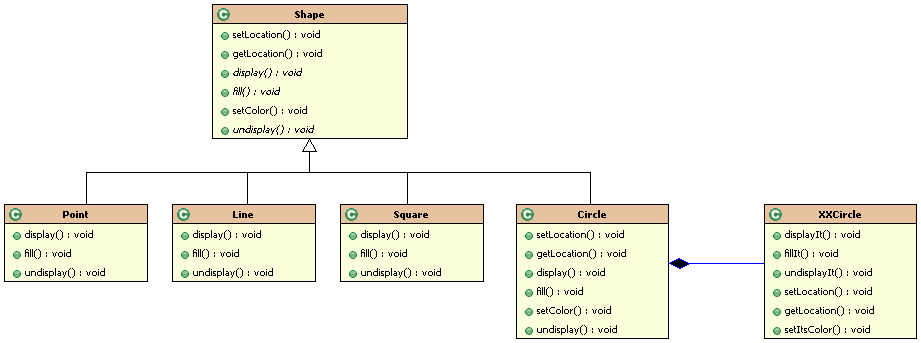

假設現在我們又被要求要去實現一個

圓

?

一個新的形狀

(

要知道,客戶對我們的要求總是在不停的變來變去的

)

。這樣,我們就又要創建一個新的

Circle

類了。我們讓

Circle

也繼承

Shape

,這樣我們就也可以對

Circle

使用多態,讓他向上轉型

(upcasting)

到

Shape

了。

Circle

類是建立好了,但是我們現在就需要對她的

display() fill() undisplay()

等等這些方法編碼了。這好像是一個痛苦的事情。

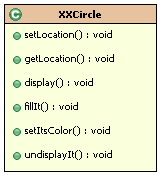

幸運的是,幾經搜索

(

就像優秀的編碼人員經常做的那樣

)

,我終于找到一個替代品

(alternative)

了。我發現

Jill

同學已經寫了一個名為

XXCircle

的類來處理和圓相關的東西

(

如圖

7-4)

。然而,很不幸的是,

Jill

并沒有象我們這樣定義

XXCircle

里的方法。她定義成了:

displayIt()

、

fillIt()

、

undisplayIt()

。

圖

7-4 Jill

的

XXCircle

類

由于我們還要用

Shape

的多態,所以我們不可能直接用

Jill

的

XXCircle

類。至于為什么,那是因為:

l?????????

不同的方法名稱和參數表

? XXCircle

里的方法名稱和參數表和我們的

Shape

類的完全不一樣。

l?????????

不是

Shape

的派生類

(

子類

)?

我們不僅僅要求方法名稱參數表要一樣還要求繼承

Shape

類。

也許我們可以試著讓

Jill

同學按照我們的需要來重寫她的

XXCircle

,改變方法名稱和參數表并且繼承

Shape

類。但是,這肯定是不現實的。因為,如果重寫了

XXCircle

,那么

Jill

以前用到

XXCircle

的地方也都要完全重寫,而且,修改正在使用中的代碼有可能會產生難以預知的副作用。

看起來我們就要達到目的了,然而卻不能用,而我又懶得自己老老實實去寫,怎么辦呢?

(

不是有句話說:“既然不能改變它,就去適應它么”?……譯著

)

與其改變

XXCircle

,倒不如適配它。

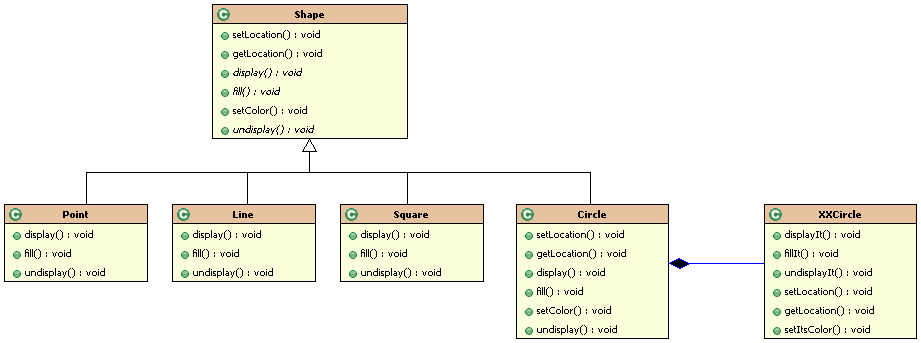

我可以從

Shape

派生一個類,這樣,這個類就可以實現

Shape

的所有接口而避免重寫

XXCircle

。具體情況請看圖

7-5

。

圖

7-5 Adapter

模式:

Circle

包含

XXCircle

l?????????

Circle

類繼承自

Shape

。

l?????????

Circle

里包含了

XXCircle

。

l?????????

Circle

把所有傳遞給

Circle

類型對象的請求全部傳遞給

XXCircle

類的對象。

圖

7-5

中

Circle

和

XXCircle

中連線末端的菱形表明

Circle

包含得有

XXCircle

。當

Circle

類的對象初始化的時候,該對象會同時初始化一個相關的

XXCircle

類的對象。如果

XXCircle

對象包含有

Circle

所需要的所有功能,那么對

Circle

對象的任何操作都將被傳遞到

XXCircle

上去執行完成

(XXCircle

不包含所有

Circle

需要功能的情況隨后再說

)

。

看下面的一段代碼

Example 7-1 Java Code Fragments: Implementing the Adapter Pattern

?2???

?3???private?XXCircle?myXXCircle;

?4???

?5???public?Circle(){

?6?????myXXCricle?=?new?XXCircle();

?7???}

?8???

?9???public?void?display(){

10?????myXXCircle.display();

11???}

12?}

?

通過

Adapter

我們就可以繼續對

Shape

使用多態了。就是說,客戶對象并不需要知道

Shape

對象所代表的確切類型。這也是一種新的封裝思想。

Shape

類封裝了形狀的確切類型。

Adapter

應用得最多的目的就是使我們能夠有機會使用多態。在隨后的章節中你就會發現其他很多模式都要求用到多態。

我們通常都會遇到和前面例子相似的情況,但是有時,被適配的對象并不一定能完全滿足我們的需要。

在這樣的情況下,我們仍然可以用到

Adapter

模式,但似乎不如先前的那么完美了。在這樣的一個情況下:

l?????????

在既存在的類中已經實現的功能可以被我們適配。

l?????????

那些我們需要但又不在既存在類中的方法,我們可以在適配器類中去實現。

雖然這樣并不如先前例子中的那么好,但是,至少,我們只需要再去實現一部分功能就可以了。

Adapter

模式使我在設計過程中不再為那些已經存在的接口所煩惱。如果一個類可以完成我的工作,那么至少從理論上講,我完全可以通過

Adapter

模式來得到適當的接口。

當你學習了更多的模式以后,你會越發發現

Adapter

的重要性。很多模式都要求某些類都繼承自同一個類。如果有既存在的類,

Adapter

模式就可以用來將該類適配給恰當的抽象類

(

就象

Circle

把

XXCircle

適配給

Shape

那樣

)

。

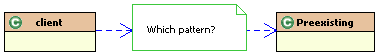

通過我們講到的這么些類,總有人會認為好像

Adapter

模式和

Facade

模式是一回事。他們都有既存在的類,都沒有恰當的接口,我們都創建了包含恰當接口的新對象。

圖

7-6

客戶對象

使用

既存在

但擁有不恰當接口

的對象

我們常聽到

包裝

和

對對象進行包裝

的說法。現在很流行對包裝遺留系統

(wrapping legacy system)

和使對象變的簡單可用的思考。

從這個高度來說,

Facade

和

Adapter

的確有點相似,他們都是進行

包裝

。但他們是不同類型的包裝方式。你應該明白這其中的小小不同。找到并理解到這其中的不同將給我們一個對模式的性質的新視角,在討論一個設計或者給設計寫文檔以使別人知道對象的確切用途的時候,這些都非常有用。讓我們來看看

Facade

和

Adapter

有何不同。

|

Facade

模式和

Adapter

模式的比較

|

Facade |

Adapter |

|

是否有既存在的類?

|

是

|

是

|

|

是否有必須實現的接口?

|

否

|

是

|

|

是否要用到多態?

|

否

|

有可能

|

|

是否需要比原接口更簡單的接口?

|

是

|

否

|

從上面的表里面可以看出:

l?????????

Facade

和

Adapter

都有預先存在的類。

l?????????

Facade

并不象

Adapter

那樣有必須實現的接口。

l?????????

Facade

模式下我并不對多態感興趣,而

Adapter

模式有時要用到多態。

(

有時,我們僅僅是因為需要實現某個特定接口而使用

Adapter

,這時,多態就無關緊要了。

)

l?????????

Facade

模式的目的是簡化接口。

Adapter

模式下,雖然是越簡單越好,但我們是根據一個既存在的類進行設計,我們不能簡化它。

總之

,

Facade

簡化接口,

Adapter

把一個已經存在的接口轉化成另一接口。

總結

Adapter

模式是一個經常使用的模式,她可以將已經存在的接口按照我們的需要進行轉換。

Adapter

模式通過創建一個包含有需要的接口的類,并把被適配的對象包含到新類當中的方式來實現。

|

Adapter

模式的主要功能

|

|

|

目的

|

把既存在的但超出控制范圍的對象匹配到一個特定接口中。

|

|

環境

|

某系統有恰當的數據和方法但是不恰當的接口。典型地用在需要繼承一個抽象類的時候。

|

|

解決方案

|

Adapter

給需要的接口提供一個對象的包裝。

|

|

參與方式

|

Adapter

適配被適配的

(Adaptee)

對象去匹配

Adapter

的目標

(Target)

對象。使得

Client

可以把被適配的對象當成目標對象使用。

|

|

結果

|

Adapter

使得既存在的對象適配新類的結構而不受其自身接口的限制。

|

|

執行方式

|

在另一類中包含現有類,并讓該類滿足接口上的要求和負責調用被包含類的方法。

|

|

|

|

|

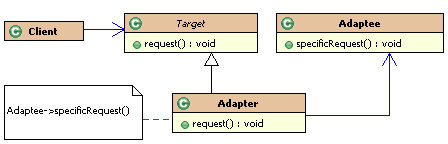

圖

7-7 Adapter

模式的通用結構

|

|

========================原文================原文==============原文=============================

The Adapter Pattern

Overview

I will continue our study of design patterns with the Adapter pattern. The Adapter pattern is a very common pattern, and, as you will see, it is used with many other patterns.

This chapter

l

????????

Explains what the Adapter pattern is, where it is used, and how it is implemented.

l

????????

Presents the key features of the pattern.

l

????????

Uses the pattern to illustrate polymorphism.

l

????????

Illustrates how the UML can be used at different levels of detail.

l

????????

Presents some observations on the Adapter pattern from my own practice, including a comparison of the Adapter pattern and the Facade pattern.

l

????????

Relates the Adapter pattern to the CAD/CAM problem.

Introducing the Adapter pattern

According to the Gang of Four, the intent of the Adapter pattern is to

Convert the interface of a class into another interface that the clients expect. Adapter lets classes work together that could not otherwise because of incompatible interfaces.

Basically, this is saying that we need a way to create a new interface for an object that does the right stuff but has the wrong interface.

Learning the Adapter Pattern

The easiest way to understand the intent of the Adapter pattern is to look at an example of where it is useful. Let’s say I have been given the following requirements:

l

????????

Create classes for points, lines, and squares that have the behavior “display”.

l

????????

The client objects should not have to know whether they actually have a point, a line, or a square. They just want to know that they have one of these shapes.

In other words, I want to encompass these specific shapes in a higher-level concept that I will call a “displayable shape”.

Now, as I work through this simple example, try to imagine other situations that you have run into that are similar, such as the following:

l

????????

You have wanted to use a subroutine or a method that someone else has written because it performs some function that you need.

l

????????

You cannot incorporate the routine directly into your program.

l

????????

The interface or the way of calling the code is not exactly equivalent to the way that its related objects need to use it.

In other words, although the system will have points, lines, and squares, I want the client objects to think I have only shapes.

l

????????

This allows client objects to deal with all these objects in the same way

-

freed from having to pay attention to their differences.

l

????????

It also enables me to add different kinds of shapes in the future without having to change the clients.

I will make use of polymorphism; that is, I will have different objects in my system, but I want the clients of these objects to interact with them in a common way.

In this case, the client object will simply tell a point, line, or square to do something such as display itself or undisplay itself. Each point, line, and square is then responsible for knowing the way to carry out the behavior that is appropriate to its type.

To accomplish this, I will create a Shape class and then derive from it the classes that represent points, lines, and squares (see Figure 7-2).

Figure 7-2? Points, Lines, and Squares are types of Shape

First I must specify the particular behavior that Shapes are going to provide. To accomplish this, I define an interface in the Shape class and then implement the behavior appropriately in each of the derived classes.

The behaviors that a Shape needs to have are as follows:

l

????????

Set a Shape’s location.

l

????????

Get a Shape’s location.

l

????????

Display a Shape.

l

????????

Fill a Shape.

l

????????

Set the color of a Shape.

l

????????

Undisplay a Shape.

I show these in Figure 7-3.

Figure 7-3? Points, Lines, and Squares showing methods.

Suppose I am now asked to implement a circle, a new kind of Shape. (Remember, requirements always change!) To do this, I will want to create a new class

-

Circle

-

that implements the shape “circle” and derive it from the Shape class so that I can still get polymorphic behavior.

Now I am faced with the task of having to code the display, fill and undisplay methods for Circle. That could be a pain.

Fortunately, as I scout around for an alternative (as a good coder always should), I discover that Jill down the hall has already written a class she called XXCircle that already handles circles (see Figure 7-4). Unfortunately, she didn’t ask me what she should name the methods. She named the methods as follows:

l

????????

displayIt

l

????????

fillIt

l

????????

undisplayIt

Figure 7-4? Jill’s XXCircle class.

I cannot use XXCircle directly because I want to preserve polymorphic behavior with Shape. There are two reasons for this:

l

????????

I have different names and parameter lists

-

The method names and parameter lists are different from Shape’s method names and parameter list.

l

????????

I cannot derive it

-

Not only must the names be the same, but the class must be derived from Shape as well.

It is unlikely that Jill will be willing to let me change the names of her methods or derive XXCircle from Shape. To do so would require her to modify all the other objects that are currently using XXCircle. Plus, I would still be concerned about creating unanticipated side effects when I modify someone else’s code.

I have what I want almost within reach, but I cannot use it and I don’t want to rewrite it. What can I do?

Rather than change it, I adapt it.

I can make a new class that does derive from Shape and therefore implements Shape’s interface but avoids rewriting the circle implementation in XXCircle (see Figure 7-5):

Figure 7-5 The Adapter pattern: Circle “wraps” XXCircle.

l

????????

Class Circle derives from Shape.

l

????????

Circle contains XXCircle.

l

????????

Circle passes request made to the Circle object through to the XXCircle object.

The diamond at the end of the line between Circle and XXCircle in Figure 7-5 indicates that Circle contains an XXCircle. When a Circle object is instantiated, it must instantiate a corresponding XXCircle object. Anything the Circle object is told to do will get passed to the XXCircle object has the complete functionality the Circle object needs (I discuss soon what happens if this is not the case), the Circle object will be able to manifest its behavior by letting the XXCircle object do the job.

An example of wrapping is shown in Example 7-1

Example 7-1 Java Code Fragments: Implementing the Adapter Pattern

Class Circle extends Shape {

…

?????? private XXCircle myXXCircle;

…

Public Circle () {

?????? myXXCircle = new XXCircle ();

}

public void display () {

?????? myXXCircle.displayIt();

}

…

}

Using the Adapter pattern enabled me to continue using polymorphism with Shape. In other words, the client objects of Shape do not know what types of shapes are actually present. This is also an example of our new thinking about encapsulation as well

-

the class Shape encapsulates the specific shapes present. The Adapter pattern is most commonly used to allow for polymorphism. As you shall see in later chapters, it is often used to allow for polymorphism required by other design patterns.

Fields Notes: The Adapter Pattern

Often I am in a situation similar to the one just described, but the object being adapted does not do all the things I need.

In this case, I can still use the Adapter pattern, but it is not such a perfect fit. In such as case

l

????????

Those functions that are implemented in the existing class can be adapted.

l

????????

Those functions that are not present can be implemented in the wrapping class.

This does not give me quite the same benefit, but at least I do not have to implement all of the required functionality.

The Adapter pattern frees me from worrying about the interfaces of existing classes when I am doing a design. If I have a class that does what I need, at lease conceptually, I know that I can always use the Adapter pattern to give it the correct interface.

This will become more important as you learn a few more patterns. Many patterns require certain classes to derive from the same class. If there are preexisting classes, the Adapter pattern can be used to adapt it to the appropriate abstract class (as Circle adapted XXCircle to Shape).

There are actually two types of Adapter patterns:

l

????????

Object Adapter pattern

-

The Adapter pattern I have been using is called an Object Adapter because it relies on one object (the adapting object) containing another (the adapted object).

l

????????

Class Adapter pattern

-

Another way to implement the Adapter pattern is with multiple inheritance. In this case, it is called a Class Adapter pattern.

The Class Adapter works by creating a new class which

l

????????

Derives publicly from our abstract class to define its interface.

l

????????

Derives privately from our existing class to access its implementation.

Each wrapped method calls its associated, privately inherited method.

The decision of which Adapter pattern to use is based on the different forces at work in the problem domain. At a conceptual level, I may ignore the distinction; however, when it comes time to implement it, I need to consider more of the forces involved.

In my classes on design patterns, someone almost always states that it sounds as if both the Adapter pattern and the Facade pattern are the same. In both cases there is a preexisting class (or a class) that does not have the interface that is needed. In both cases, I create a new object that has the desired interface (see Figure 7-6).

Figure 7-6 A Client object using another, preexisting object with the wrong interface.

Wrappers and object wrappers are terms that you hear a lot about. It is popular to think about wrapping legacy systems with objects to make them easier to use.

At this high view, the Facade and the Adapter patterns do seem similar. They are both wrappers. But they are different kinds of wrappers. You need to understand the differences, which can be subtle. Finding and understanding these more subtle differences gives insight into a pattern’s properties. It also helps when discussing and documenting a design so others know precisely what the object(s) are for. Let’s look at some different forces involved with these patterns (see the following table).

|

Comparing the Facade pattern with the Adapter pattern |

Facade |

Adapter |

|

Are there preexisting classes? |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Is there an interface we must design to? |

No |

Yes |

|

Does an object need to behave polymorphically? |

No |

Probably |

|

Is a simpler interface needed? |

Yes |

No |

This table tells us the following:

l

????????

With both the Facade and Adapter pattern, I have preexisting classes.

l

????????

With the Facade, however, I do not have an interface I must design to, as I in the Adapter pattern.

l

????????

I am not interested in polymorphic behavior with the Facade; whereas with the Adapter, I probably am. (There are times when we just need to design to a particular interface and therefore must use an Adapter. In this case, polymorphism may not be an issue

-

that’s way I say “probably”.)

l

????????

In the case of the Facade pattern, the motivation is to simplify the interface. With the Adapter, although simpler is better, I am trying to design to an existing interface and cannot simplify things even if a simpler interface were otherwise possible.

Sometimes people draw the conclusion that another difference between the Facade and the Adapter pattern is that the Facade hides multiple classes behind it whereas the Adapter only hides one. Although this is often true, it is not part of the pattern. It is possible that a Facade could be used in front of a very complex object while an Adapter wrapped several objects that among them implemented the desired function.

Bottom line

: A Facade simplifies an interface while an Adapter converts a preexisting interface into another interface.

Summary

The Adapter pattern is a frequently used pattern that converts the interface of a class (or classes) into another interface, which we need the class to have. It is implemented by creating a new class with the desired interface and then wrapping the original class methods to effectively contain the adapted object.

|

The Adapter pattern: Key Features |

|

|

Intent |

Match an existing object beyond your control to a particular interface. |

|

Problem |

A system has the right data and behavior but the wrong interfaces. Typically used when you have to make something a derivative of an abstract class. |

|

Solution |

The Adapter provides a wrapper with the desired interface. |

|

Participants and collaborators |

The Adapter adapts the interface of an Adaptee to match that of the use the Adaptee’s Target (the class it derives from). This allows the Client to use the Adaptee as if it were a type of Target. |

|

Consequences |

The Adapter pattern allows for preexisting objects to fit into new class structures without being limited by their interfaces. |

|

Implementation |

Contain the existing class in another class. Have the containing class math the required interface and call the methods of the contained class. |

|

|

|

|

Figure 7-6 Generic structure of the Adapter pattern. |

|

?

?